Writing: Motifs in Fiction

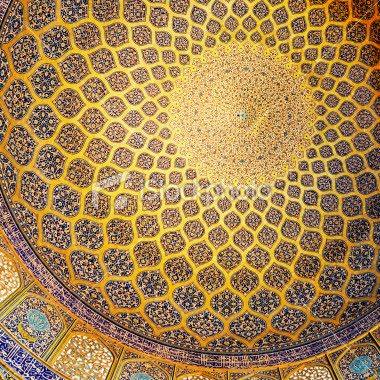

A motif is a repetitive design in art. It's fairly obvious what this means in the visual arts; a motif is a repeating squiggle or shape, often tiled or layered over and over throughout the painting or mosaic. In non-figerative art, the motif may be the dominant feature.

The term "narrative motif" is a metaphor borrowed from the visual arts, but it's a little less obvious how to employ a motif in fiction than it is in art. A "motif" can also overlap with other writing techniques, like "metaphors," "archetypes," and "themes," since a motif can be all of those at once.

Motifs reenforce archetypes and themes through the use of interlinked metaphors.

In certain genres, particularly fantasy, motifs are ready at hand because the entire genre is archetypal by its nature: magic, quests, lost princes, warrior princesses, assassins, dragons and thieves... virtually every fantasy trope is replete with a rich history of myth and legend and previous fantasy blockbusters that layer in expectations.

Sophomoric writers rail against these expectations, while more deft writers play off of them.

Motifs can unify the sentence-and-paragraph level of a story with the archetype and theme of the larger work. For instance, suppose your theme is something like: It's better to light a candle than to curse the dark.

(Yes, when you phrase it baldly, a theme is going to sound like a truism. That's because many wise people have lived and died and struggled with the same issues you have and left a reef of their wisdom for you to grow your own struggles on.)

In your book, you might have a character state the theme directly (often, it will be a side character who states the theme early on) and in new words. However, even if the theme isn't directly stated, even if you, the author, don't discover the theme until after you've written the novel, the motifs can reenforce and layer in the theme.

At the sentence level, remembering your theme, you pick words, phrases and metaphors that reinforce it. You can speak of your heroine, "standing her ground between the children and the writhing nest of shadowy wyverns, like a candle in the window standing against the dark. She nearly melted with fear, but deep within her glowed the conviction that she must fight for the children--even if she lost her own life."

Now, you don't have to hammer the same nail in every single paragraph. You don't want to get ham-fisted about it. Besides, it's good to have three or four motifs in a story, perhaps tied to the protagonist, romance interest, other supporting characters, and villain, so you aren't simply returning to the same metaphor endlessly. The pattern repeats, but with interludes of other repeating patterns, to create a unique design.

One advantage of drawing on archetypes is that every archetype comes with a repertoire of associated symbols that make great motifs.

A layered, complex theme doesn't feel bald and trite, like a truism does. The simple image becomes profound because of the larger design it is woven into, just as a vaulted ceiling with a simple repeating image becomes profound by its scale and grandeur.

In my series The Unfinished Song, there are overarching themes and motifs, but each book also has its own theme, which I discovered by starting with motifs and weaving a pattern from them. It's perfectly acceptable to discover your theme by writing about it! In fact, it helps avoid the temptation to turn a theme into something didactic or propagandistic.

In Initiate, for instance, there is a hidden secret about the heroine's magic--or lack. It is never stated directly why she--and her whole clan--have no magic. (She must find that out in a later book.) However, there are two side plots about supporting characters which indirectly hint at the issue. One is her friend Gwenika, who is being sickened by a hex. The other is Gremo, a man Kavio (the hero) encounters, who is cursed to drag a huge boulder in a circle, around and around, endlessly.

When I began the series, I already knew the secret hex on Dindi's clan, what it was and why it existed, but I didn't know about Gwenika or Gremo.

By the way, motifs don't always have to be visual. Did you know that every book in The Unfinished Song has a "taste"? It's a flavor that I return to over and over throughout the book. I don't draw attention to it; I hope that it flavors the story subtly, in the subconscious of the reader.

Can you guess what flavor the first book is? You can read Initiate for FREE here.

Comments